Should we make students apologize for damage they cause?

As an elementary vice-principal, one of my roles is to support teachers with student misbehavior. This work doesn’t consume all of my time, but it has its moments.

Even in the best of elementary schools, little humans have problems. They make mistakes. They hurt feelings. They harm other bodies. They throw sticks and rocks and break stuff.

The challenges are inevitable — a rite of passage for any parent or educator. How we respond, however, is a matter of discussion.

Two boys have just lost their tempers on the playground, throwing punches and kicking each other. Two girls have exchanged cruel words during a collaborative project in class and can no longer work together.

How should the well-meaning teacher or administrator proceed?

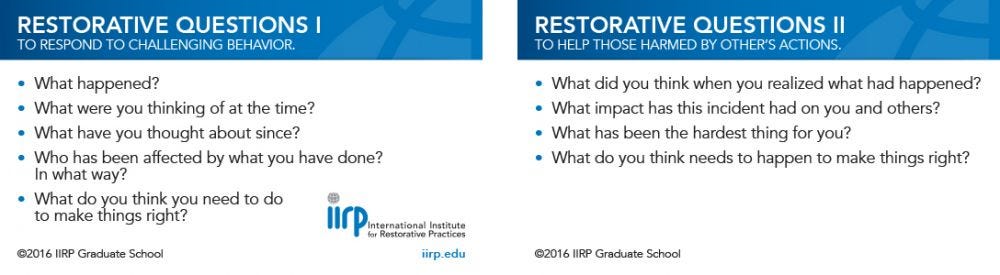

In a sea of great resources available to educators, I’m grateful to the International Institute for Restorative Practices for these practical conversation prompts. I use them with students often.

Set 1 (on the left) guides my questions with students who have clearly committed offenses against others, the building, or something in the school environment.

Set 2 (on the right) guides my questions for students who appear to be more on the receiving end.

Note the last question of each set: What do you think you need to do to make things right? and the slightly different What do you think needs to happen to make things right?

Those questions are so critical, because they signal our mission. They reveal our community values.

Contrary to school discipline systems of old, it’s actually not my top priority to mete out swift, precise, and just punishment — as satisfying as that might feel. We’ve learned that formulaic consequence systems — as elaborate, heavy, and consistent as they may be — do not typically lead to lasting character change.

And they don’t contribute to school culture, either.

Before I lose you, it’s not that I’m against consequences and disciplinary actions. Sometimes, they’re quite appropriate, and I’ve delivered them many times.

But when something has been broken, punishment isn’t the top priority. Instead, it’s healing, repair, and restoration.

What do you think you need to do to make things right?

What do you think needs to happen to make things right?

So … should we make students apologize?

First, let’s take a moment to agree that none of us can really force a student to apologize if they don’t want to. We can’t move their mouths and make words come out. And we certainly can’t apply coercion, stress, or the threat of punishment to elicit apologies that mean anything, anyway.

So we’re not really talking about “forcing” students to do anything.

But should apologies be required?

When I’m confronted with hard policy decisions, I like to return to this tried-and-true filter:

- Is this best for learning?

- Is this best for kids?

These are the two questions that we come back to as educators. They form the filter for just about any K-12 policy decision that you can think of.

So when I consider conflicts that occur in my elementary school, when I look at cases where students have harmed other students, staff members, or property, I think about the steps that must be taken in order to make wrong things right. To repair what was broken.

And friends, I just can’t see a world in which harms have been repaired and relationships restored that does not involve apologies.

It’s true in marriage. It’s true in families. It’s true in business and on our staff teams.

When problems occur and people are hurt, we name the problem and take steps to address it. That’s Relationships 101.

Sure, some student apologies will be fake or only half-authentic.

- But all verbal apologies still require looking at another human being.

- They still require naming the offense.

- They still require explaining why the offense was a problem.

- They still require committing to do better.

- And they still require asking for forgiveness.

Colleagues, these are life skills. These are skills that our children will need in order to survive and thrive as partners, parents, and leaders.

I have no interest in depriving our children of the character-building opportunity that is apologizing.

So no, as long as I’m in my current role, an apology won’t be a mere option for the next student who punches another. There won’t be any skating by big mistakes as if they never happened.

There won’t be any you-can-apologize-if-you-want-to choices for kids.

Obviously, cool-down periods are often appropriate. Where safety is threatened, physical separation can be a higher imperative.

An apology is not a thing to rush without first re-establishing basic trust and respect.

But generally speaking, student apologies should be a requirement.

Because at my school, and at yours, we own our mistakes, and we repair the things we break.

That is who we are and this is what we do.

That’s the culture I want.

And that’s why I’m in favor of forced apologies.

Leave a comment