Seven moves you can make to save your sanity and empower your students.

What’s one student behavior that you’ve found challenging recently?

Whether you’re new to teaching or you’ve been around for a couple of decades, we’ve all got room to grow in terms of how we interact with students and manage our spaces effectively.

This was my message at a workshop I co-led with colleague Vanessa Neufeld last Friday. No one in our profession has this down perfectly. The school life just isn’t that neat and tidy.

We’re ALL developing learners.

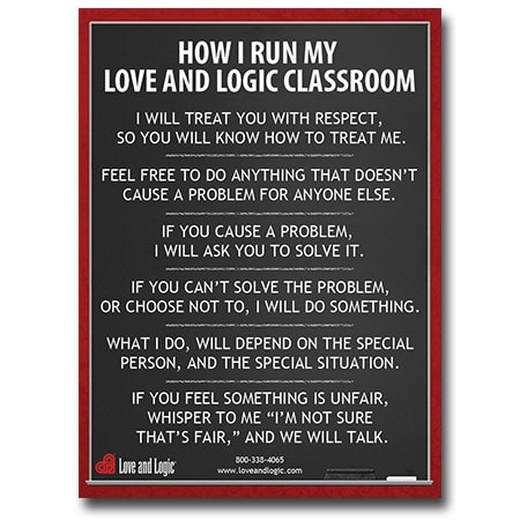

Enter Love and Logic, a research-driven, whole-child philosophy that has guided educators and parents since the seventies. Though applications evolve with the times, its simple tools continue to equip educators and empower children in profound ways.

I’ll get to some of the essential skills in a moment, but first, let’s set the stage with two primary rules of Love and Logic.

Two primary rules of Love and Logic

- Rule 1: Educators set limits in loving ways without anger, lectures, threats, or repeated warnings. Love allows students to grow through their mistakes.

- Rule 2: When students misbehave and cause problems, adults hand these problems back in loving ways. Logic allows them to learn from the consequences of their choices.

These rules lay a critical foundation for the essential skills to come.

Now, are you ready to add some tools to your classroom management toolkit?

Let’s go.

Seven essential skills that save teacher sanity and empower students to solve their own problems

Skill 1: Neutralize student arguments.

We’ve all had the moment in the middle of an activity when a student wants to get into it with us. Like really get into it.

They’re upset. They think we’re being unfair. They’re furious that we “always” or “never” do X, Y, or Z.

And they want to argue their case, loudly, passionately, and persistently.

There’s only one problem. We’re in the middle of an activity, and we’ve got 24 other students to support. We don’t have the time or capacity to hold court in the moment.

Love and Logic tells us to respond in two ways:

- Use a one-liner response — not a paragraph.

- Deliver the one-liner with empathy — not sarcasm.

One-liners to practice might include:

- “I know you’re frustrated.”

- “Thank you for sharing that feedback.”

- “I appreciate your opinion, but that’s not an option.”

- “Let’s continue this conversation when your voice is calm like mine.”

- “If you’d like to talk about this more, let’s meet at lunch break or the end of the day.”

None of these one-liners are eye-rolling, sarcastic, or dismissive. They’re stated with care, concern, and respectful eye contact.

Then we move on.

Skill 2: Delay consequences for student misbehavior.

Crash!

Your students were goofing around in a corner of the room, and they knocked an empty aquarium onto the floor, where it shattered.

Onlooking students are shocked, and your blood pressure spikes as you absorb what has just happened.

For the educator, it can feel absurdly important to react clearly, strongly, and promptly in the moment. To quickly assess wrongdoing and assign a big, proportional consequence that will satisfy onlookers and strike fear into the hearts of the careless wrongdoers right away.

Love and Logic advises against the knee-jerk consequence, for the following reasons:

- It’s difficult to react well when we’re upset.

- We don’t have all the information we need to make good decisions.

- It’s challenging to come up with appropriate actions in the moment.

- We may be taking ownership of the problem too quickly rather than handing it back to students.

- We don’t have time to think carefully about the unique needs or learning profile of the students involved.

- We don’t have time to put together a reasonable plan to carry it out (including making sure that the consequence doesn’t require punishing ourselves unnecessarily).

- We deprive the student of a learning opportunity by removing their agency. We’re not even giving them a chance to think about the question: how can I make this right?

There’s no rush to make a big decision after a mistake has been made. Instead, try lines like these ones:

- “This is not okay. We will have to figure out how to solve this problem later.”

- “Oh no — I’m so sad this happened. I am going to have to do something about this later. Don’t worry about it.”

- “I am feeling really angry right now. I need time to calm down and come back into the green zone we make a decision about what happens next here.”

- “This was not a great decision. I would like to ask our principal for advice about what to do next. We will talk about this further tomorrow.”

Take a deep breath, and take your time with the problem, colleague. Things will go better for all concerned.

Skill 3: Empathize with students.

As the old saying goes, students don’t care what we know until they know that we care.

So how can we show them that we care? How can we demonstrate that their problems matter to us?

Empathetic one-liners can sound like this:

- “That sounds really frustrating.”

- “Oh no! Tell me more about that.”

- “That must have felt overwhelming.”

- “It sounds like you think that was unfair.”

- “I can tell that this situation made you feel really uncomfortable.”

To empathize with students, we don’t have to agree with their take on things. We just have to show that we’re listening.

Skill 4: Set limits and save our sanity with enforceable statements.

Try not to use threats or bribes. We’ve all used them, but they’re not not effective.

Threat: “If you don’t stop talking, NO ONE is going to the playground!”

Bribe: “If you all stop talking, we can all go to the playground!”

Instead, focus on your own behavior and let your students know what YOU will do.

- Instead of “Don’t shout in the classroom!” try “I speak with students when they use calm voices.”

- Instead of “We will not leave the classroom if the class stays this noisy!” try “We will leave the classroom once the class volume is zero.”

- Instead of “Stop arguing with me!” try “I’ll be glad to discuss this with you as soon as you are ready to listen.”

These are almost the same messages, aren’t they?

But with slight adjustments in our language and phrasing, we’re no longer begging or bargaining with students. We’re simply letting them know what we will do.

And that, colleagues, remains within our control.

Skill 5: Offer choices to avoid power struggles

Most students crave degrees of autonomy, freedom, and independence, just as we all do. The more choices we build into their learning, the greater their sense of agency will be, and the less likely they are to argue when the teacher’s instructions don’t allow for choice.

It’s helpful to think of every choice we offer students as a deposit, every demand as a withdrawal. It’s easier to make withdrawals like “We’re all going to read this short story now” when there’s a balance in the account.

With this in mind, let’s be flexible when and where we can. We were planning for students to work individually on this next learning activity, but could they work in partners?

This is also where Universal Design for Learning shines.

UDL encourages multiple ways of engagement, representation, action and expression. Choice boards and similar mechanisms give students options: How would they like to interact with content and show what they’ve learned?

Depending on the learning target, there may be a lot of room for alternatives.

One warning to keep in mind: It’s important to avoid framing an instruction as a choice when it’s not really a choice.

“Would you like to clean up now?” is better expressed as “Okay, it’s time to start cleaning up.”

Or, to offer students some agency in this context, we can ask “Do you think I should set the 5-minute timer or the 10-minute timer for clean-up?”

Make frequent choice deposits, and instruction withdrawals will flow more naturally.

Skill 6: Guide students to solve their own problems.

Do any of these distress signals sound familiar?

- “I don’t have a pencil.”

- “I can’t find my homework.”

- “Suzie hit me.”

- “I don’t know what we’re supposed to do.”

- “My Chromebook is dead!”

We live in an age when parents and educators are told to shield our children from anxiety. It’s implied in many different ways, so when our students encounter problems, our instinct is often to run to the rescue.

But rescuing our students isn’t actually empowering, and it reinforces a victim mindset in students. Whenever we solve a problem for a student that they could have solved themselves, we’ve robbed them of an opportunity to think for themselves and learn that they ARE capable.

Handing problems back to students might sound like:

- “Oh, I’m sorry to hear that. What are you going to do about it?”

- “I have some ideas for you. Would you like to hear them?”

- “Some students in your position have tried …. Do you think that could work?”

- “Let me know how that goes for you.”

Allowing students to solve their own problems is also a key piece of a restorative justice approach.

When students make messes, damage property, or hurt others, we don’t need to invent an obscure consequence. They simply need to own the natural consequence of their actions: clean up the mess, replace what was lost, repair what was damaged, or restore the relationship.

- A student spilled paint on the floor during art class? They should clean it up.

- A student broke their Chromebook screen? They should pay for the repairs.

- Two students were playing catch with a chair and put it through the drywall in a classroom? They should patch it up and paint over it. (This actually happened in my room one year.)

As we help our students own their problems and work through the natural consequences of their choices, Love and Logic warns us not to destroy the teaching value of the logical consequence by …

- Saying things like “This will teach you a lesson.”

- Displaying anger or disgust.

- Explaining the value of the consequence.

- Moralizing or threatening.

- Talking too much.

- Feeling sorry and “giving in.”

- Contriving an additional consequence for the purpose of “getting even” or “making this sting more.”

The less talking and explaining we do, the more we’re letting the natural consequence speak for itself.

Skill 7: Develop strong relationships with students.

I’ve saved the best for last. At the heart of the Love and Logic philosophy is RELATIONSHIPS.

As educators, it’s not healthy or helpful to try to become friends with our students. But education is a people business, and relationships count for a lot. It’s hard for children to learn outside of them.

Books can and have been written about this, so I’ll just boil this one down to two simple strategies: noticing and collecting.

Strategy 1: Noticing

Noticing is a strategy that essentially boils down to this: teachers build bridges with difficult, hostile students by signalling that they have our attention.

We signal this by consistently approaching the student, smiling, and dropping innocent, neutral-value (non-praising) observations like this:

- “Hey, I noticed that you play the violin.”

- “Hi Mike. Are those new shoes?”

- “Hi Vicky. I noticed that you made the basketball team.”

- “Hey, I noticed that you’re interested in chess.”

Observe: there’s no material for an argument here. We’re simply sharing an observation.

Sometimes, the student may want to talk further about this area of passion or interest. Or they may not. We’re not there to press the issue — we’re just sowing another seed of connection.

To do this well, we need to read the room. It may not be a strategy to try with a student when they’re surrounded by peers or in the throes of a challenging moment. And we probably don’t want to try this more than once in a day.

But when we use this strategy consistently in quieter, calmer times, it has a way of slowly building trust.

Strategy 2: Collecting

I’m jumping out of the Love and Logic philosophy a little bit here to bring in a term I’ve learned from noted psychologist Gordon Neufeld: collecting.

Collecting our students is as simple as making eye contact, smiling (showing we are happy to see them), and extending a greeting that includes their name. That’s it.

Dale Carnegie famously said that the most powerful word in the English language is a person’s name.

A smiling “Good morning, Tim” or “Welcome, Kristine” may not seem like a big deal, but it is.

I’m convinced that a high percentage of conflicts and power struggles in the classroom are avoided by teachers who have collected each of their students before or at the beginning of class.

And listen, I know that in the life of the school day in the middle and upper grades, it can be hard — well nigh impossible — to stand at the door and greet each student by name before every single block.

But give it a try, educators. You’ll have more fun, you’ll come to love and appreciate your students more, and they’ll reciprocate.

Everything just flows more smoothly once you’ve established this simple connection with your students.

Final thoughts

By now, perhaps you’re wondering if this is a paid endorsement. It’s not. I have no affiliation or communication of any kind with the authors of Love and Logic, and I earn nothing if you buy the book, but here it is.

I just know that these skills work in my world.

No, the students in my school aren’t perfect. But we find that by following these seven habits, building trusting relationships with kids, and allowing them to own their problems, our community is better for it.

Leave a reply to N/A I N/A Cancel reply