Learning targets take some good-natured abuse these days on TikTok and Instagram reels. And hey, I can chuckle at some of the shots.

No, learning targets won’t save your life. They won’t solve your classroom management problems. Simply posting them on the wall won’t be enough to magically improve your students’ engagement and learning.

But I will absolutely insist that learning targets CAN save you time, mental energy, and sanity.

Here’s why and how in a nutshell. They can reduce, simplify, and focus your assessment activities.

Less is more.

You’re not a street sweeper, teachers. It’s not your job to inhale everything in sight.

No, you’re an eagle-eyed detective. Instead of grading everything and every part of what your students do, you’re only looking for particular pieces of evidence.

And that, my friends, can make all the difference in the world.

Let me show you what I mean.

Example 1: A sixth grade solar system activity

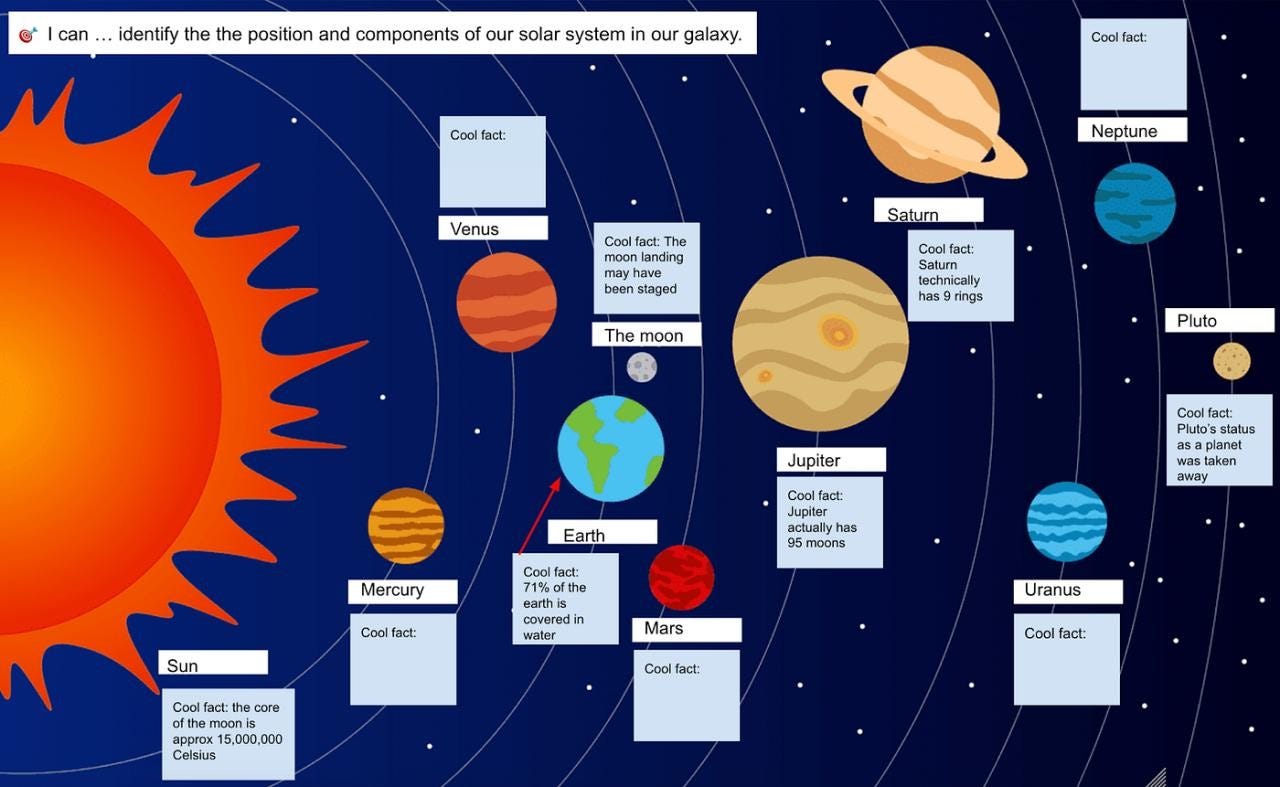

Let’s take this hypothetical learning activity for sixth grade Science students. I’ve asked students to 1) label each planet correctly and 2) use the text box feature to add one interesting fact about each planet, moon, and star.

Those are the activity instructions. But pay close attention to the learning target.

It’s taken from our sixth grade Science curriculum: 🎯 I can … identify the position and components of our solar system in our galaxy.

Now here’s the key. Does the learning standard require that students describe each major component of our solar system? Nope. That skill may appear elsewhere in the curricular documents, but not in this particular standard.

So am I going to take valuable minutes to verify each fact that my students decide to include for each celestial body? No, I am not.

All I need to do here is complete a quick scan to confirm that students have correctly identified the components of the solar system. That’s IT. That’s all the evidence I need.

So instead of taking 2–3 valuable minutes per student to carefully review (and research) each completed solar system poster, I’m taking about 5–10 seconds to verify that the names of the planets appear correctly.

I just cut my hour of assessment work down to two minutes, which may also mean that the assessment can be completed and recorded during class time (it depends on how you plan to use the data, of course).

Am I conning or cheating students by operating this way? Absolutely not. To suggest so is to suggest that asking my students to learn more about each planet is a waste of time.

It’s the old grades-as-wages mindset that says that students must be paid for any and every completed activity. It’s a terrible paradigm and it reinforces backward thinking about the value of learning.

Don’t fall for it.

Example 2: A fourth grade English activity

Let’s say that you’re teaching fourth grade English and you’ve just completed some learning around literary devices. You want to assess student learning against a classic learning target: 🎯I can … use similes properly in my writing.

Many kinds of learning activities would provide the evidence we need to assess student proficiency against this curricular standard. But let’s say that you choose to go with something quick and simple that requires students to do some writing: write three paragraphs about your family, using at least three similes effectively.

Students begin their writing, and — because you used the Google Classroom ‘Make a Copy for Every Student’ feature — you’re able to jump from one student’s work to the next in real time while they write, offering feedback and assessments of their learning as they write.

You read that correctly: you’re making assessments — not in the late hours of the evening after you’ve put your own kids to bed — but as they write. Here’s what I mean.

Let’s say I hop into Narissa’s Google Doc. She’s writing away, perhaps 1–2 paragraphs in. I’ll make sure to give her some quick encouragement. But I don’t have to stop there. If I can already spot three similes used effectively in context, I can assess her proficiency, record it, and move on.

Is Narissa’s third paragraph wasted if I don’t read it or never come back to it? Not at all. To suggest so is to suggest that students can’t benefit from writing by themselves, which is absurd.

Of course they can. Our students need to write so much more than they do today.

As teachers, we offer feedback, guidance, and encouragement when and where we’re able. But it’s silly to suggest that they can only grow when we’ve put their work in its entirety under our sacred magnifying glasses.

The big idea: learning targets tell us which evidence to examine

Remember: we’re not street sweepers, teachers. We’re detectives.

The next time you assess your students’ work, start with the learning target. Precisely which pieces of evidence do you need to examine carefully and thoughtfully?

Spend your mental energy on that, and — at least for this particular learning activity — ignore the rest.

You’ll be saving your sanity in the process.

Even better? Your students will receive feedback and assessments that are actually helpful.

I call that a win-win.